We as dispatchers must face head-on the issue of secondary traumatic stress and recognize that in our line of work, it is normal to be affected by the stories we hear on a daily basis. How then do we “reclaim” our joy and peace amid the chaos and the sadness and the difficult calls that have become our norm?

A little over a year ago, I watched a movie that just stuck with me in a terrible way. The movie centered on a teenaged girl who suffered months of beatings and torture at the hands of a caregiver she was entrusted with, and ultimately died from the abuse. I remember back then that I wanted to look away from so many scenes as I felt my stomach do about a dozen flips and turns in sheer disgust at the depravity of the evil this child was subjected to, but I also couldn’t stop myself from watching it all the way to its bitter end. After all, it was just a movie.

Except, it wasn’t just some movie, it was a cinematic retelling of a true crime story. And I made the mistake of looking up the actual story on Wikipedia which revealed to me in unfortunately generous and graphic details that the true story was far more traumatic than the mere two hours I had endured watching.

Over the next week, I cried more times than I could count, barely ate, hardly slept, and kept replaying scenes from the movie over and over like a bad loop in my head. There was a part of my brain that scolded myself for being this emotionally wrecked over a film. I mean, it was silly right. I didn’t know this girl. I had no real connection to her story or anything even remotely in common with the tragedy that she suffered. I just happened to be triggered by seeing or hearing anything about child abuse or neglect, and her story was certainly triggering for me.

I felt guilty just trying to move on with my life. I was physically exhausted and feeling mentally drained through the whole ordeal. I remember being mid-conversation with my sister one day and her saying something that drew a laugh out of me. Then this thought popped into my head, totally out of the blue, that I didn’t deserve to laugh. It wasn’t fair that I could laugh when that girl was dead and would never laugh again on this earth.

Nothing seemed to make sense in my life and suddenly nothing was interesting to me. Everything reminded me of that movie and no matter how hard I tried to bury it with other thoughts, it kept resurfacing. At work I was also struggling to not be cynical or devoid of empathy with my callers because the world was a sick, sick place with real monsters and the complainant calling about a petty disagreement with their landlord over the rent didn’t possibly deserve my sympathy, am I right?! Wrong! What in the world was my problem?

Secondary Trauma

It turns out that what I was experiencing wasn’t so strange after all. In fact, in our line of work it is an all-too common occupational challenge. It’s called secondary trauma. Secondary trauma aka secondary traumatic stress (STS) or compassion fatigue is a state of emotional distress that results from repeated exposure to persons who have been traumatized or from hearing firsthand accounts of traumatic events.

It didn’t matter that it wasn’t my trauma or my story. It was a story that I had heard many times over. The sixteen-year-old alleging through heavy sobs that their dad and stepmom was verbally abusive towards them. The twelve-year-old reportedly covered in welts that ran for shelter to a neighbor’s house after a beating by their grandfather. The eight-year-old calling from the porch of their home because their intoxicated mother got upset about the mess in their bedroom and kicked them out of the home for the night.

As 911 telecommunicators, we are often the first people to hear the pain, the raw emotions, the fear, and trauma that someone is feeling in some of the worst, lowest moments of their lives. Sometimes it’s as if we’re experiencing it too, right along with them, and we feel the stress that they feel. The problem though is that while they might in the end get some kind of closure, those of us on this side of the headset oftentimes do not have the luxury of getting closure to be able to process what has happened and move on. In the absence of having all the facts, we speculate, and we fill in the gaps with what could have, may have, or probably did happen.

The Way Back

So just how high is the cost of caring “too much” and how can anyone find their way back from secondary trauma?

Professionals more prone to developing STS are:

- First responders (911 telecommunicators, law enforcement, firefighters, paramedics, etc.)

- Healthcare workers

- Child protection advocates or social workers

- Other professions that involve having frequent exposure to or contact with survivors of traumatic events (crisis line operators, journalists, insurance claims adjusters, lawyers, jurors, etc.)

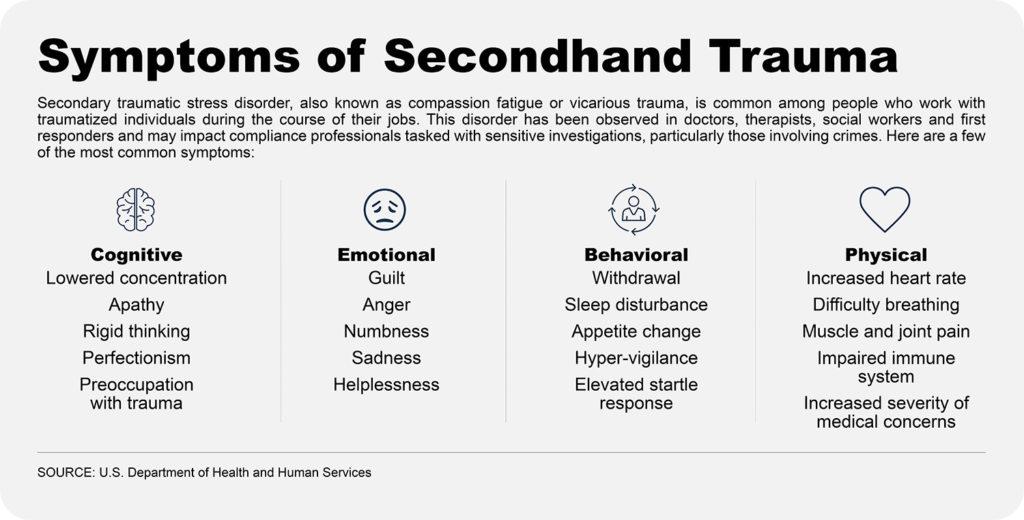

Symptoms can be cognitive, emotional, behavioral, and, yes, even physical. They can present at any time and unlike burnout which can result from the long-term stress of doing a job in a non-supportive work environment, STS can occur after just one incident of an indirect exposure (having knowledge of a traumatic incident, helping, or wanting to help someone who’s been traumatized).

Signs can look like: irritability, tiredness, anhedonia, physical illness, sadness, depression, anger, persistent anxiety, difficulty sleeping, feelings of hopelessness or loneliness. These symptoms can be exacerbated by increased workloads, isolation in the work environment, and recurring contact with the traumatized first party or parties.

*The graphic is not even all-encompassing of symptoms of STS.

Scenario #1

To put it into perspective, imagine this scenario:

Dispatcher A has been on the job for two years now. She lost her father a few years ago to suicide and ever since then calls involving suicide threats or attempts have been very triggering for her, although, she mostly can manage to process the call and put it out of her head enough to move onto the next call. Then one day she receives a call from a mother crying because she has discovered her young adult daughter lying in a tub full of water with two slit wrists. Dispatcher A goes home and finds over the next few weeks that she is unable to eat, sleep, and just enjoy life without hearing that mother’s cries and screams in her head. She is considering quitting altogether.

Scenario #2

Now here’s another scenario:

Dispatcher B is a 15-year-veteran in the industry. He’s heard it all, experienced it all, and taken some of the worst of the worst calls. He’s earned a few stork pins for a few successfully delivered babies and won a pair of life-saving awards for a couple of CPR saves in his career, but he’s also experienced his share of death and loss and calls where the outcome just didn’t come out the way that he had hoped.

Well, today he got a call from a panicked babysitter reporting that the five-month-old baby in her care is choking and turning a dreadful shade of blue. He does what he has done a dozen times before, relays the medical instructions for dealing with a choking infant with precise accuracy and an almost superhuman air of total calm. But the efforts aren’t enough, and the paramedics say that the infant was gone by the time they arrived on scene.

It’s not his first rodeo; it’s not the first baby he couldn’t save in time. Yet, something about this call just absolutely wrecks him and he doesn’t think that he has it in him to do this job much longer.

It’s just a call, right? They have no emotional connection to these people or to their lives. Why would these calls affect them as much as they do? That is what compassion fatigue looks like for those of us in 911. In a profession where our services are so needed and the demand is extraordinarily high, it can be all too easy to neglect our own trauma and stress.

Talking Through it

For me, finding my way back from STS involved three very conscious decisions on my part.

First, I had to decide to talk about it. Resiliency doesn’t have to be a solo act. Secondary traumatic stress is an isolating condition. It will make you feel like no one in the world could possibly understand what is happening to you and that your feelings are invalid. My feelings were perfectly normal to be having, and I wasn’t truly alone. I had a network of support and peers to lean on.

If you recognize that you might be experiencing STS, then realize that the sooner you talk about those feelings with someone, the sooner your brain can accept that it’s normal to feel this way but not normal to stay in these feelings. Opening up and having an honest and transparent discourse about your symptoms is not the whole fight, but it is the beginning of the fight. Talking about the guilt that may be weighing on your chest, crushing your willpower to move on to the next call, the next situation, the next day, helps you to face it and acknowledge the power it has assumed over you. We take away from its power when instead of isolating ourselves, we connect with those who we love and trust, or talk to a mental health professional, and tell them exactly what we are going through.

Through the Thick of it

Second, I needed to decide within myself before my next shift that I was going to have “my best day today.” I decided that I was going to stop beating myself up for a story that I couldn’t change, no matter how sad it was and how unfortunately tragic of an outcome it had. I couldn’t go back in time to undo the ending of that young girl’s tragedy. I couldn’t give up my happiness to give her back hers. I could instead vow to treasure every minute of life and decide to live a purposeful, meaningful existence (and few professions are as meaningful to society as the work we do in public safety).

Just like with the calls we take as 911 telecommunicators. We can’t undo the bad calls, we can’t give some of these people back their loved ones, or rewrite history to take the pain and trauma away. We can vow though to give every caller 110% of ourselves and choose to have a good day for them. The parent of the choking child today deserves our compassion, our care, and our diligence in getting them the right help to the right place. And if we are still reliving the choking baby call from several months ago, we cannot possibly be fully in the moment to be our best, most effective self for our caller who needs us right now.

We Appreciate You!

Finally, I had to start making a conscious effort to celebrate my work, the small victories, and the large ones, every chance that I got. An important part of finding your way back from STS is taking time to “clap for yourself.” In our line of work, if something goes wrong, we blame ourselves. If something goes right, we give all the credit to everyone else, because certainly they’re the heroes, never us on this side of the radio, this side of the headset. We struggle more than ever with coping with the negative side of this job because we rarely allow ourselves to bask in the positivity of our work or all the good endings that we help facilitate. I had to tell myself that so many calls I have taken as a 911 telecommunicator has had amazingly successful outcomes, and many of my callers have gotten the help they needed because I stayed on the line with them and helped to de-escalate a terrible situation. I had to remind myself that not everyone can do what I do for a living and yet I do it every day with a smile on my face. So, remember to thank yourself for showing up and being just plain awesome! Remember how super you are and that it takes only the best of the best humans on this planet to wear this headset!

Secondary traumatic stress can feel like a black gaping rabbit hole, but the good news is there is hope for finding your way out of it.

About the Author

Samantha Hawkins

Samantha Hawkins is a seasoned professional in the field of public safety communications. Her career in this field began in 2015; since then, she has made significant contributions to the industry. Samantha is a certified PSAP Professional and Quality Assurance Evaluator, showcasing her field expertise. She is also highly experienced in training others for public safety communications, demonstrating her commitment to sharing her knowledge and skills with others.